At a commenter’s recommendation—and I’ve forgotten who it was, so speak up in the comments—I’ve been reading Charlotte Dennet’s Follow the Pipelines: Uncovering the Mystery of a Lost Spy and the Deadly Politics of the Great Game for Oil.

As warned, the author is sometimes annoying and the mix of personal interests with geopolitics is frustrating at times, but it has proved a worthwhile slog through the history and geopolitics of the Middle East from the standpoint of Western neocolonial schemes. The scheming continues to the present, in constantly shifting shapes. What I’ll offer here is a summary of Chapter 8: The Hidden History of Pipeline Politics in Palestine and Israel. The details are convoluted, so I’ll keep it general.

The background is in the energy shift from coal to oil—for purposes of making war. England’s fleet was a key to maintaining its global empire, and the efficiencies of oil over coal meant that it was necessary to transition the fleet from coal to oil to keep up with and ahead of the rest of the world’s naval powers. In addition, oil was needed for the as a source of toluene—necessary for the production of TNT. England, in common with all Western European nations lacked local sources of oil, so it needed to go global to obtain it. And, of course, the ability to control the sources of oil and exclude access to oil by other nations became a major concern.

England had, by 1907, obtained access to rich oil fields in Iran (Persia). However, those oil fields were in close proximity to the Ottoman Empire’s provinces in what is now Iraq—which posed a threat to the security of the British controlled pipelines. In addition, the British were eager to secure additional sources of oil, in Iraq. Wikipedia sketches out the situation before WW1, in Mesopotamian campaign:

Persia had previously been divided by the British and Russian Empires into spheres of influence in 1907, with these oil fields under British influence. The oil pipeline to transport the Persian petroleum ran alongside the Karun River into the Shatt al-Arab waterway, with refineries based on Abadan Island in the area. However, much of the Shatt al-Arab also flowed through Ottoman-owned Mesopotamia, making this pipeline vulnerable to invasion. The petroleum in this region was vital for Britain's new line of oil-fired turbine based dreadnoughts as well as toluol for the production of explosives. In addition to oil, Britain wanted to retain its dominance of the Persian Gulf, show support for local Arabs, and demonstrate power to the Ottomans, … In addition to these factors, growing German influence in the region caused by the creation of the Berlin-Baghdad railway was of concern to London.

Pretty classic “Great Game” stuff.

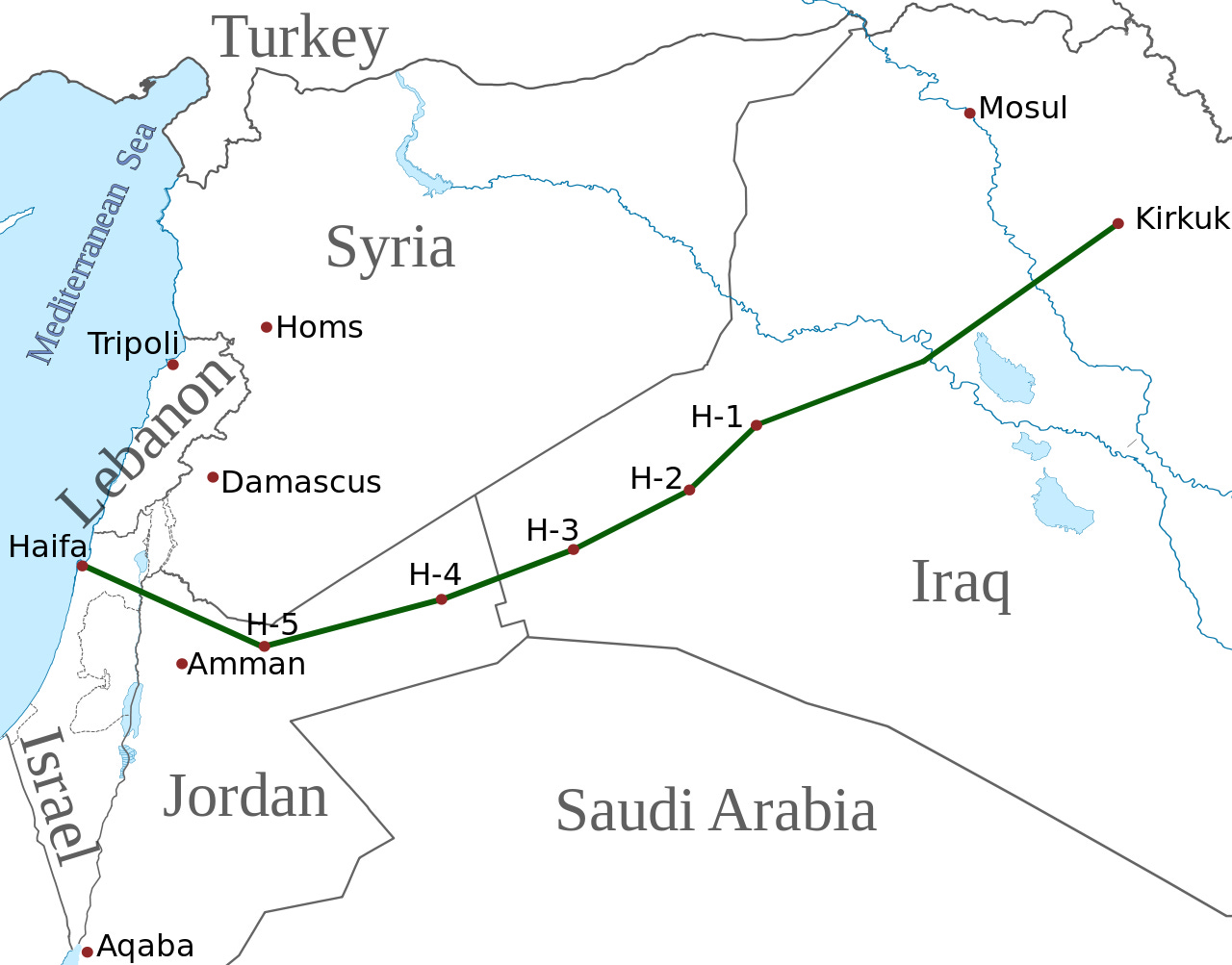

Already by 1912 the British and Indian war offices had been planning for operations in the Middle East, with their eyes on both Mesopotamian (Iraq) as well as the security of the Suez canal. Once WW1 got underway, people like Winston Churchill were quick to enunciate the importance of securing all of present day Iraq, in order to control its oil fields. According to Churchill, Iraq was “a first class war aim.” Forward strategic thinkers also realized that, once the Iraqi oil fields were secured there still remained the question of transporting it back to England. Far cheaper than shipping oil around the Arabian Peninsula, up the Red Sea, and through the Suez Canal would be moving the oil by pipeline from Iraq to the Eastern Mediterranean seaboard. Since the French were already active in Lebanon, the logical site for such a pipeline terminus—once the Ottoman Empire was dismembered—would be the port of Haifa in Palestine. All this would also entail control over the local Arab population.

Once WW1 started, those plans were put into play. However, given that the British were heavily occupied on the Western Front, implementing this scheme involved the heavy use of Indian troops, as well as some dodgy diplomacy with the Arabs. The most populous parts of the region were still under the control of the Ottoman Empire, but the Arabs were eager to assert their independence. Britian offered the Arabs promises in that regard in return for their help against the Turks. The tricky part came after the war, when Britain reneged on its promises to the Arabs and attempted to exercise control over the entire region (excepting the French “zone of influence” to the north) from the Mediterranean to Persia, through a slapped together framework of “mandates” and “zones of influence”, established over the heads of the Arabs. This was necessary because it was foreseeable that the Arabs would want to have control over their own lands and resources.

At this point, the middle of WW1, a new factor entered the picture: the Zionist movement. The Zionist movement had already been active for decades, but was constrained by Muslim control over Muslim lands, including Palestine. The Muslims—Turks and Arabs—were aware of Jewish ambitions for Palestine and were adamantly opposed to a Zionist state in Palestine. However, the Zionists had powerful friends in Western Europe—the Rothschild banking family in both their London and Paris branches. As it happened, the Rothschilds of each branch were not only immensely influential in finance, they were also very much involved in the oil ventures of their respective countries (the French, at that time, were focused on the Caspian area). Thus it was that, over the heads of the Arabs, the Zionists were able to leverage the support of the London Rothschilds to induce Britain to promulgate the ambiguously worded Balfour Declaration (1917), promising a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

This was not at all simply a romantic venture of British religious goofs. It was very much about securing a pipeline route for Persian and Iraqi oil to the Mediterranean coast—preferably at Haifa, in Palestine. The Zionists were fully aware of what was driving the British, and expressly suggested that a Jewish Palestine would be a major advantage for the British—not only in securing a terminus for their planned pipeline, but also in securing the the Suez Canal and exerting influence over Egypt from a secure land base.

I’ll skip over most of the interwar years and the jockeying for influence in the Middle East. Suffice it to say that, after WW1, the French and British predictably stabbed the Arabs in the back—despite Arab help in defeating the Turks, and in spite of promises of independence. They divvied up the entire region, with the French having major influence in Lebanon/Syria and the British in the region from Palestine to Persia. This, along with the Balfour Declarations promise of Arab land to the Jews, led to large scale unrest and even (in Iraq) significant warfare. Nevertheless, the Iraq Petroleum Company Pipeline did get built and operated, with a terminus in Haifa, from 1935 to 1946:

Naturally, the pipeline became a target for Arab nationalists, who resented the looting of their resources through the lopsided “mandates” and “zones of influence,” with the attendant sweetheart deals for the oil companies. In the end, after the establishment of the state of Israel, the Iraqi government, having asserted its independence from Britain, stopping oil shipments.

During WW2 the issue of Jewish emigration to Palestine became a major issue. The West hoped to send Jewish refugees to Palestine in furtherance of the scheme to establish a Western aligned country that would help preserve Western influence in the region over the energy resources. The Arabs, led by King Ibn Saud, were adamantly opposed to increased Jewish emigration to Palestine. Exactly how this worked out isn’t entirely clear, but the British and Americans declined Jewish appeals to bomb rail transport to Auschwitz—on frankly dodgy grounds. This had nothing to do with Ibn Saud. What appears to have occurred is that the Roosevelt administration that the additional Jews who were saved might end up in the US, due to Arab opposition to Jewish emigration to Palestine. So the US took no steps at all to end the killing at Auschwitz, despite having bombed neighboring areas. Of course, the rest of the story is that the West did end up facilitating the emigration of Jews to Palestine, against the wishes of the actual inhabitants of the country.

From 1948 on the IPC pipeline, Kirkuk to Haifa, has been shut off. However, that doesn’t mean that the dream has died. In fact, it appears that the war on Iraq was motivated in large part by Neocon dreams of resurrecting the pipeline by installing a “friendly”, i.e., puppet, Iraqi regime that would cooperate. And they told us it was about weapons of mass destruction.

Israel seeks pipeline for Iraqi oil

US discusses plan to pump fuel to its regional ally and solve energy headache at a stroke

The revival of the pipeline was first discussed openly by the Israeli Minister for National Infrastructures, Joseph Paritzky, according to the Israeli newspaper Ha'aretz .

...

US intelligence sources confirmed to The Observer that the project has been discussed. One former senior CIA official said: 'It has long been a dream of a powerful section of the people now driving this administration [of President George W. Bush] and the war in Iraq to safeguard Israel's energy supply as well as that of the United States.

...

... In 1975, Kissinger signed what forms the basis for the Haifa project: a Memorandum of Understanding whereby the US would guarantee Israel's oil reserves and energy supply in times of crisis.

Kissinger was also master of the American plan in the mid-Eighties - when Saddam Hussein was a key US ally - to run an oil pipeline from Iraq to Aqaba in Jordan, opposite the Israeli port of Eilat.

The plan was promoted by the now Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, and the pipeline was to be built by the Bechtel company, which the Bush administration last week awarded a multi-billion dollar contract for the reconstruction of Iraq.

That all fell through, too. Nevertheless, energy is still very much a factor—now, in Israel’s brutal war on Gaza.

The Great Game in the Holy Land

How Gazan Natural Gas Became the Epicenter of An International Power Struggle

Back in 1993, when Israel and the Palestinian Authority (PA) signed the Oslo Accords that were supposed to end the Israeli occupation of Gaza and the West Bank and create a sovereign state, nobody was thinking much about Gaza’s coastline. As a result, Israel agreed that the newly created PA would fully control its territorial waters, even though the Israeli navy was still patrolling the area. Rumored natural gas deposits there mattered little to anyone, because prices were then so low and supplies so plentiful. ...

[British Gas] promised to finance and manage their development, bear all the costs, and operate the resulting facilities in exchange for 90% of the revenues, an exploitative but typical “profit-sharing” agreement. With an already functioning natural gas industry, Egypt agreed to be the on-shore hub and transit point for the gas. The Palestinians were to receive 10% of the revenues (estimated at about a billion dollars in total) and were guaranteed access to enough gas to meet their needs.

Had this process moved a little faster, the contract might have been implemented as written. In 2000, however, with a rapidly expanding economy, meager fossil fuels, and terrible relations with its oil-rich neighbors, Israel found itself facing a chronic energy shortage. Instead of attempting to answer its problem with an aggressive but feasible effort to develop renewable sources of energy, Prime Minister Ehud Barak initiated the era of Eastern Mediterranean fossil fuel conflicts. He brought Israel’s naval control of Gazan coastal waters to bear and nixed the deal with BG. Instead, he demanded that Israel, not Egypt, receive the Gaza gas and that it also control all the revenues destined for the Palestinians — to prevent the money from being used to “fund terror.”

Continual Israeli obstructionism—in spite of the fact that Gaza’s Hamas government had agreed to Israeli demands to send payments through the NY Fed—has led directly to the Israeli war on Gaza, in both economic and military aspects.

With Egyptian cooperation, Israel then seized control of all commerce in and out of Gaza, severely limiting even food imports and eliminating its fishing industry. As Olmert advisor Dov Weisglass summed up this agenda, the Israeli government was putting the Palestinians “on a diet” (which, according to the Red Cross, soon produced “chronic malnutrition,” especially among Gazan children).

When the Palestinians still refused to accept Israel’s terms, the Olmert government decided to unilaterally extract the gas, …

Hamas retaliation, including rocket attacks on Israel, has led to a stalemate over the gas fields—and ever more violent Israeli attacks on the Gazan population: Operation Cast Lead, Operation Returning Echo, Operation Protective Edge, etc.

Interestingly, things took a turn in 2013. The Palestinians took a page from the book of over nations who had disputes with Israel over offshore gas fields, and who were being intimidated by the Israeli military:

... The Palestinian Authority then followed the lead of the Lebanese, Syrians, and Turkish Cypriots, and in late 2013 signed an “exploration concession” with Gazprom, the huge Russian natural gas company. As with Lebanon and Syria, the Russian Navy loomed as a potential deterrent to Israeli interference.

That’s where things stand today:

The British gas exploration rights to Gaza marine gas field expire in 2024. After this Gaza could grant these rights to Russia. This is something very concerning to Washington. Keep in mind, the Biden administration was also behind the destruction of Nord Stream....

Wheels within wheels. The long and the short is that the American Empire has more or less stepped into the shoes of the British Empire, in terms of attempting to control the Middle East—only with a lot more firepower. Western neocolonialism continues for the time being.

The book was my tip. It is a clunky read but in terms of tying threads together it's a good place to start.

Great post, Mark! Thank you. I hope the evidence you and others are providing will be widely shared and will make a difference - I hope it will help people recognize this evil and help them put a stop to it. I think this is a very good companion piece to the post you did recently:

https://meaninginhistory.substack.com/p/big-picture-historical-background

One of the "bridge" paragraphs between the two posts is in that one, as follows:

"Following stipulations of Rhodes’ Will, his collaborators sparked WWI to dismantle a threatening Germany, carve up Europe, secure + expand colonial holdings by acquiring much of Ottoman Empire, giving them its oil holdings + secure Palestine as military buffer to Suez Canal."

It seems strange for "normals" like us to contemplate the idea that access to and extraction of natural resources such as oil and gas could provide so strong an impetus for the barbarism and inhumanity and wars we have seen over the years in the ME and Asia and Africa. But here we are. Why is it always deemed necessary for the "civilized" nations of the West to take by force that which could be peacefully negotiated or bought or sold? To dictate rather than to listen? To attack rather than to aid? As opposed to the "spreading civilization" mantra put forward by the Brits of the 19th and early 20th Century and Teddy Roosevelt, I don't consider such attitudes and actions either representative of Christianity or of civilization.